Time to talk... about MHM

Menstruation is a taboo subject for women and girls in East Africa; many women and girls consequently miss out on education, or other productive activity, due to fear of embarrassment from their male peers. What's worse is that the social stigma has materialised: a study by Abanyie et al, 2021, showed that, within the municipality of Wa in Ghana, all the schools lacked menstrual hygiene facilities. In another Ghanaian municipality: West Gonja, only 30.8% of the schools had assigned sites for changing of menstrual materials, and no school had menstrual hygiene materials available for emergency use.

Although hygiene and clean water is covered by UN SDG 6, women have specific hygiene needs, particularly during menstruation, and childbirth. During childbirth, only a third of women in Uganda, 18% in Kenya, and 7% in Tanzania could access improved water and sanitation in health facilities (Gon et al., 2016, Rombo et al, 2017). While I don't reflect on this topic for this post, it also requires critical attention. With unsafe access to latrines to change their pads, and unaffordable prices for menstrual health products, the consequences are dire: infection, a compromised education [school absenteeism] and girls engaging in transactional sex to receive menstrual hygiene products (Kearon, 2021). As a female, I cannot imagine facing these challenges, and have always taken for granted, menstrual hygiene management (MHM), which is what this post will explore.

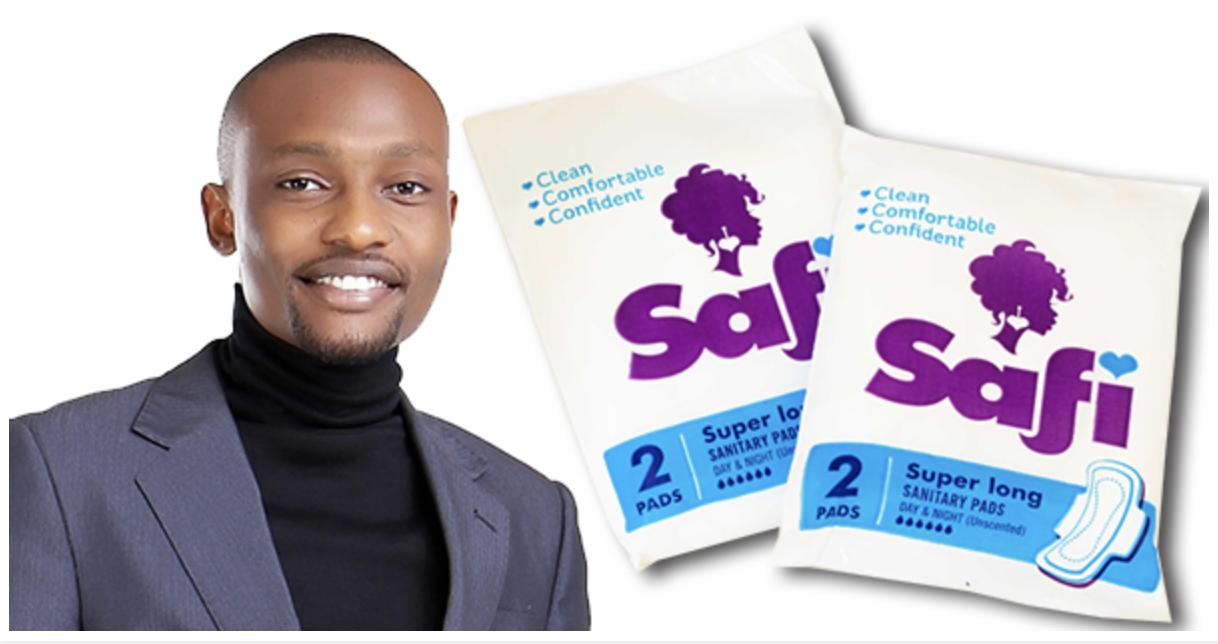

MHM relates to the "range of actions and interventions that ensure women and girls can privately, safely, and hygienically manage their monthly menstrual flow with confidence and dignity" (Giles-Hansen, Mugambi and Machado, 2019). A key approach has been to develop affordable and reusable sanitary pads:

The Global Women's Water Initiative is an organisation which teaches grassroots rural women economic and technical solutions within water and sanitation, which is a sector they are often left out of (remember how men predominantly oversee latrine construction?). One goal is for these women to become socialpreneurs, by making reusable inexpensive sanitary pads, which simultaneously empower women to lead in the water & sanitation movement, as well as generating their own income. This knowledge can be passed onto other women, who can produce such innovations for their own community.

This was a really comprehensive post and I thoroughly enjoyed reading it! I especially appreciate the inclusion of examples of potential solutions as stories surrounding period poverty can often be overwhelmingly negative. At the beginning of this post you describe how periods are a 'taboo' for many women and girls in East Africa, how do you think periods could be destigmatised in East Africa?

ReplyDeleteHi Helen, thank you for your kind comments! That's a great question- For an gender-inclusive approach, I think that both school boys and girls should be educated on the WASH sector and why it is necessary for their right to hygiene and sanitation, under UN SDG 6. This would help them understand why WASH facilities for menstrual hygiene management is needed, such as soap and water access, and disposal facilities, which destigmatises the taboo.

Delete