Introduction: Who has the right to water?

Welcome to my blog on Water and Gender, where I shall use Africa as my case study. The interlinkage of water and gender is multi-faceted, covering a wide span of topics, such as politics, sanitation and, most recently, climate change. It therefore seems appropriate to pay attention to water and gender as a key relationship, particularly where women's voices have not been present enough within the (water) policy arena, and where they face significant disadvantages against the backdrop of increasing water scarcity.

There are a few key issues worth discussing, which will come later into play, for my other blog posts. Firstly, women are seen to have primary household responsibility in collection of domestic water, which has become an increasingly concerning issue for two reasons. As time spent on collecting water tends to be quite long, and arduous, this means that particularly girls of school age often must compromise their right to education (Article 26 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights- UDHR), as well as facing corporeal injustice, through excessive heat exposure (Williams et al, 2022). Secondly, the exposure to sexual violence has proliferated, where access points to water sources have become a key site for men to target women, contravening Article 3 of the UDHR: the right to security. These issues are just the tip of the iceberg and have demonstrated that a presence of a water source does not necessarily mean access to water itself. If the UN Sustainable Development Goal 6, which promotes safe and universal access of water for all, is to be achieved- is it time to critically review and resolve these issues?

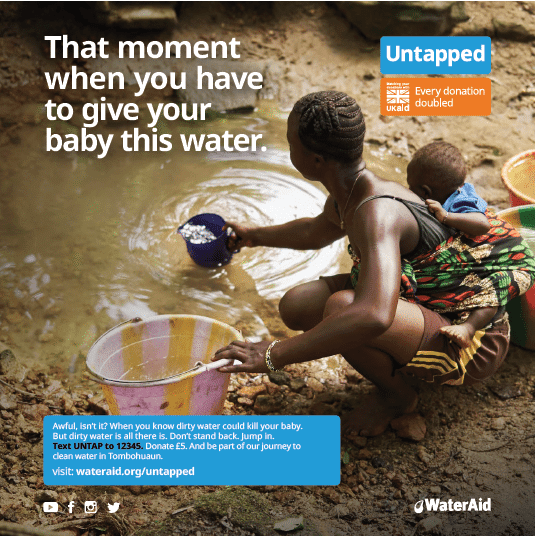

Figure 1: A WaterAid advert which displays the archetypal image of African women as vulnerable in the face of a 'water crisis' and requires Western intervention through donations. The caption in the advert has obscured the opinion and everyday experience of African women who are confronting lack of access to water.

So, what I wish to avoid doing in this blog is showcasing the "doom and gloom" of Africa's access to water- I feel that if I were to do this, I would only concretely prove Wainaina's point. That's why I set out to see how the relationship between water and gender has an alternative narrative and carry out a “relational analysis of power and authority in shaping access to water, through community, market, and state level institutions” (Rao et al, 2019: 16), through a gendered perspective.

Comments

Post a Comment