Women as Water Collectors

"Although donors and governments often use the term gender when addressing different needs with respect to water resources, they usually mean women". (Rathgeber, 1996)

Reading this quote couldn't be truer, and before researching more thoroughly into this topic, I'm guilty of the same charge.

This blog post will explore how women as water collectors in areas of high water scarcity face complex conflicts at water access points with men, and the solution.

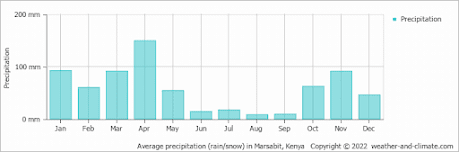

Focusing on Marsabit County located in Kenya, here's the hard facts: the county has not received rain for over three years and over one million livestock have been lost to drought, and its average amount of annual precipitation is 693mm, and faces extreme dry spells from June to September.

As a result, conflict often breaks out between different groups over water allocation at water access points.

A key example of this is the conflict between livestock herders and domestic users. Livestock herders often tend to be men, whilst women, who are recognised as water collectors for the household, are domestic users (Yerian et al, 2014).

"Men explained that livestock were often given priority access to the water because they had a greater distance to travel and that women could collect water for domestic use after the livestock left" (Yerian et al, 2014).

As a result, water collection points become a site of contestation considering livestock users, and men specifically, have demoted the importance of women's water collection for staple household activities such as cooking and bathing. Additionally, the imbalance of power between men and women has created a risk of contracting disease, considering livestock may contaminate the water whilst drinking (Mazet et al, 2009), which threatens the health of women. Since there has been a decline in public water access points because of water sources drying up, water collectors are forced to share the same water access point unequally, due to diverging interests, which becomes a gendered concern.

Another key issue regarding water collection is the time and distance taken for water collection.

This graph represents the dire situation that as climate change takes its toll and water access points dry up especially in the dry season, so does the burden of walking for a greater distance to collect water. This problem directly concerns women, who are the primary water collectors, and face heat exposure as a health risk during the dry seasons when there is an increased walking distance.

The solution? A water ATM machine!

Video explaining the implementation of an automatic water vending machine using a chip coin, to address the issue of women walking for hours to collect water.

The use of a privatised chip coin serves as a water vending machine, which addresses the issue of water-sharing conflict amongst users, the threat of pathogenic contamination from livestock watering and increased distance and time to collect water. While this seems all well and good, the chip coin determines access to water, which means income has a significant role- where 63.7% of Marsabit's population are classified into the category of absolute poverty, this should be an issue to consider with privatised water provisioning.

This was a very interesting blog to read! I particularly liked the use of the graph, it really helped to visualise the statistics regarding household water distances. To make the blog a bit clearer to read, I'd suggest putting mini headers within the essay!

ReplyDeleteHi Kavitri, thanks for your comments and I'm glad you found the post interesting- your suggestion was very helpful, and I will try using mini headers next time!

Delete