Concluding Thoughts

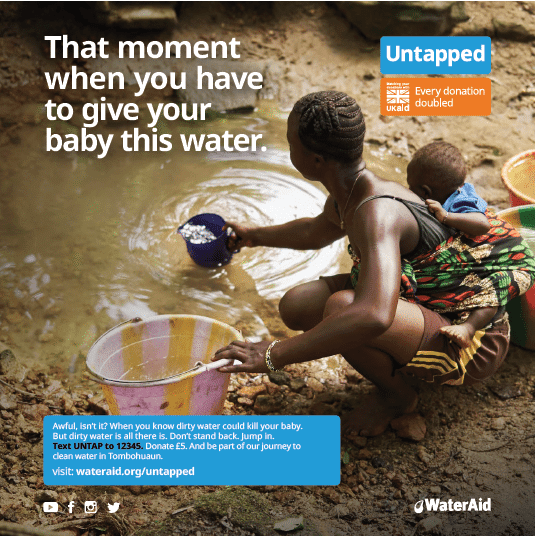

In my first blog post, I referenced Wainaina’s satirical conceptualisation of how Africans, especially women, are stereotypically framed as helpless and without a voice. I hope that this blog has disproved that point, particularly when it comes down to water and development. Before writing this blog, my perception of the relationship between water and gender was the plenitude of burdens associated with women's water collection, as well as lack of access to WASH facilities. Generally speaking, I would argue that this is what comes to mind for most people, but the blog stimulated me to delve into other topics such as women's uneven access to climate smart agriculture (irrigation) in water-stressed regions, which I had never even previously considered. The interconnected nature of the water-development paradigm is so rich, that despite a focus on gender, I was able to explore other thematic areas which was challenging at times but rewarding...